Mental health is an essential part of your wellbeing. Even though you can’t see it in the same way as physical wellness, your mental health is just as real and important.

Mental health is made up of how you feel, think, behave and what you believe about yourself. It can affect your thoughts, emotions, focus, relationships, sleep, work and even cause physical symptoms.

For this reason, mental health and physical health are interconnected, as one can easily affect the other.

Who is affected

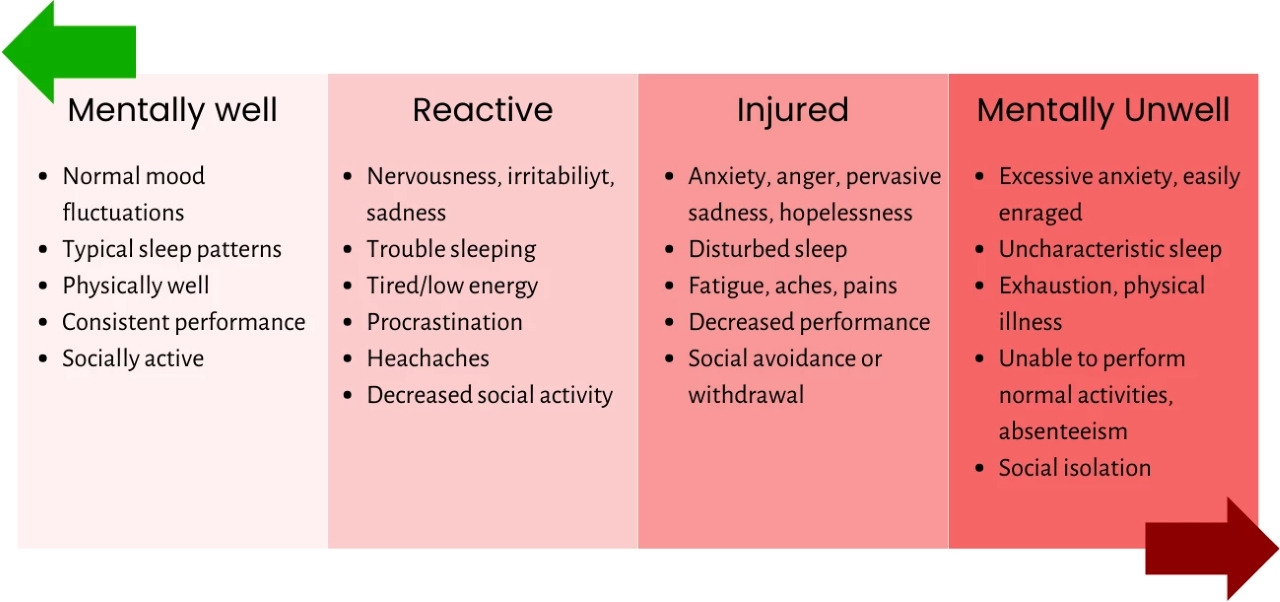

Everyone has mental health – that includes you and every person who has ever lived! Mental health is part of being human and it is likely to fluctuate at different times in your life, or even throughout different parts of each day. Therefore, mental health is best thought of as being on a continuum. The figure below shows the spectrum of thoughts and behaviour generally associated with feeling mentally well, all the way through to feeling mentally unwell.

It is normal to move up and down this continuum depending on life stressors and circumstances. Whilst we’d like to be operating at our best all the time, this isn’t necessarily realistic. Being human means going through hard times and feeling unpleasant emotions.

Spending short times in the ‘reactive’ or ‘injured' parts is an indicator that we need to look after ourselves. If you notice you are becoming stuck there, unable to bounce back, or you are sliding down the continuum and unable to recover from the deeper red zones, it may be an indictor your mental health needs some attention.

Common mental disorders

Anxiety

Anxiety disorders are one of the most common mental disorders in Australia, with 17% of the population, or one out of six people, experiencing symptoms of an anxiety disorder in the last 12-months.

We all get anxious from time to time. This is a normal response to stressful events and usually passes when the stressor, for example public speaking, is over.

If anxiety increases to the point of getting in the way of life’s activities or is prolonged or excessive, it may be impacting your life enough to be considered an anxiety disorder.

Signs and symptoms of anxiety

Please note that this list may not cover all signs and symptoms

Behaviour

- Start to avoid usual activities

- Seeks reassurance from others

- Increased use of substances

Thoughts

- Can’t stop worrying

- Mind racing or going blank

- Drops in memory and concentration

- Indecisive/ self-doubt

Feelings

- Stressed/tense

- Overwhelmed

- Feelings of dread/ urge to flee

- Irritable/ quick to anger/ impatient

Physical Signs

- Dry mouth/ sweating

- Tense muscles/headaches

- Rapid, shallow breaths

- Chest pain/racing heart

- Knotted stomach/ butterflies

The neuroscience of anxiety

Neuroscience is helping to shed light on what’s happening in the brain when people experience anxiety disorders.

Parts of the brain that are affected include:

- The prefrontal cortex (PFC): The PFC has an important role in regulating emotions. The PFC is essential for logical reasoning and executive functioning.

- Amygdala: A small almond-shaped region of the brain involved in fear and emotional processes.

- The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA): The HPA axis refers to the neuroendocrine (i.e. hormonal and nervous system) pathway that ignites the stress response. It explains how an initial stressor is perceived by the brain and communicated to the adrenal glands, which release stress hormones (such as cortisol) needed for ‘fight and flight’.

Neuroscience research is showing us that changes in these important regions occur when people experience stress and anxiety disorders. For example, neuronal dendrites (the ‘branches’ of brain cells) whither in the PFC (reducing our capacity for logical reasoning and emotional regulation) and strengthen in the amygdala (enhancing our fear response). Evidence also points to dysregulation of the HPA axis in anxiety and stress disorders, making you more prone to seeking threats in the environment and responding to these.

Depression

Depression is a disorder that affects how we think, feel and act in unhelpful ways. Around 8% of Australians are considered clinically depressed.

While we all feel sad, moody or low from time to time, some people experience these feelings intensely, for long periods of time (weeks, months or even years) and sometimes without any apparent reason. Depression is more than just a low mood – it's a serious condition that affects your physical and mental health.

Findings from neuroscience

Physical activity is associated with less anxiety, depression and burnout.

Regular exercise is linked to better blood flow to the brain and production of new cells in the hippocampus, a part of the brain which has shown a tendency for shrinkage in people with depression

Sleep deprivation is associated with a higher risk of developing depression.

Signs and symptoms of depression

Please note that this list may not cover all signs and symptoms

*Please note that these signs and symptoms are not designed for diagnosis, or to replace appropriate treatment from a qualified health professional. Please follow the helping steps to access support if you are concerned about your mental health.

Behaviours

- Withdrawing from others

- Less communicative

- Not participating in usual activities or hobbies

- Not as productive

Feelings

- Hopeless

- Irritable/ Frustrated

- Unhappy/ Miserable

- Loss of pleasure or enjoyment

Thoughts

- Thoughts are negative or critical;

- “I can’t do this”

- “I’m a failure”

- “I don’t want to wake up”

Physical Signs

- Feeling tired/ rundown

- Sleep changes

- Appetite changes

- Aches/pains

About PTSD

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a range of symptoms and reactions that someone can have as a result of going through a traumatic event. Not everyone who experiences a trauma develops PTSD, about 5-10% of Australians will struggle with PTSD at some time in their life.

PTSD is considered one of the stress related disorders, and if someone thinks they may have it, it is important to be formally assessed by a mental health professional.

Signs and symptoms of PTSD

Please note that this list may not cover all signs and symptoms.

Risk factors for mental disorders

There is still much we need to learn and discover about mental health. Much of our research at the Thompson Institute is about better understanding of how the brain changes when we feel mentally unwell – and what we can do help that.

Some people develop a mental illness completely out of the blue. For others, there are some factors that increase the risk of mental health disorders, such as:

- Stress: Particularly prolonged and chronic

- Stressful life events: Divorce/relationship breakdown, illness, grief/loss, financial pressure

- Genes: Family history of mental illness

- Minority experience: racism, sexism, ableism etc

- Insecure or unsupportive employment conditions

Reflection activity

Whilst the risk factors list shows us some common risk factors, stress can affect people differently. For example, some people feel extraordinarily stressed when their home or office is untidy, whilst others could not care less about a messy desk, or dirty cups in the sink.

Take a moment to think about what personally stresses you?

- Is it email?

- Certain conversations with certain people?

- Trying to fit too much in on the weekend?

- Or something completely different?

It may help to write your common stressors down in journal or on a piece of a paper to clearly identify the factors that may be influencing your stress levels.

Protective factors

Early intervention is also very powerful. Taking action when you first notice that your mental health is slipping supports the road to recovery. It’s also never too late to ask for help!

There are also a variety of lifestyle factors that can protect our mental health:

- Sleep

- Routine

- Exercise

- Nutrition

- Mindfulness

- Social connection

- And, a sense of purpose/meaning

Take a look at the Wheel of Wellbeing pictured opposite and identify a few of the protective lifestyle factors that resonate most with you. See if you can integrate more of these activities into your daily life.

Practical Tips

- Identify your personal risk factors for mental health and minimise them where possible

- Identify your protective factors for good mental wellbeing and maximise them however you can

- Consider what part of the ‘wheel of wellbeing’ would benefit you most and take some small, actionable steps to support this area of your life

- Take a screenshot of the Mental Health Helplines and support options. You just never know when you or somebody you know may need it