Life can change in a flash. Or in Jenny’s case, a war that destroyed her life in Ukraine and sparked a sequence of serendipitous moments that led her to Australia and the University of the Sunshine Coast.

If, on the 23rd of February 2022, you’d asked 20-year-old Yevheniia Nekrasova, who goes by “Jenny,” what her life would look like in 12 months’ time, she would have forecast a very different scenario.

A student at Karazin Kharkiv National University, the second-oldest university in Ukraine, Jenny was a foreign languages major, studying English and Chinese. She had a natural talent for languages, even winning a scholarship to study in China in 2019 (though COVID-19 derailed those plans).

She lived on campus in the heart of Ukraine’s second-largest city, Kharkiv, located just 42 kilometres from the Russian border. Despite ominous warnings and rumours that had started circulating in late January, Jenny says nobody was really paying attention as a war seemed “extremely unlikely to happen.”

In the pre-dawn hours of February 24, while most of the city slept, the explosions began. Jenny and her best friend, who was also her roommate, woke to the sounds of missiles blasting the city.

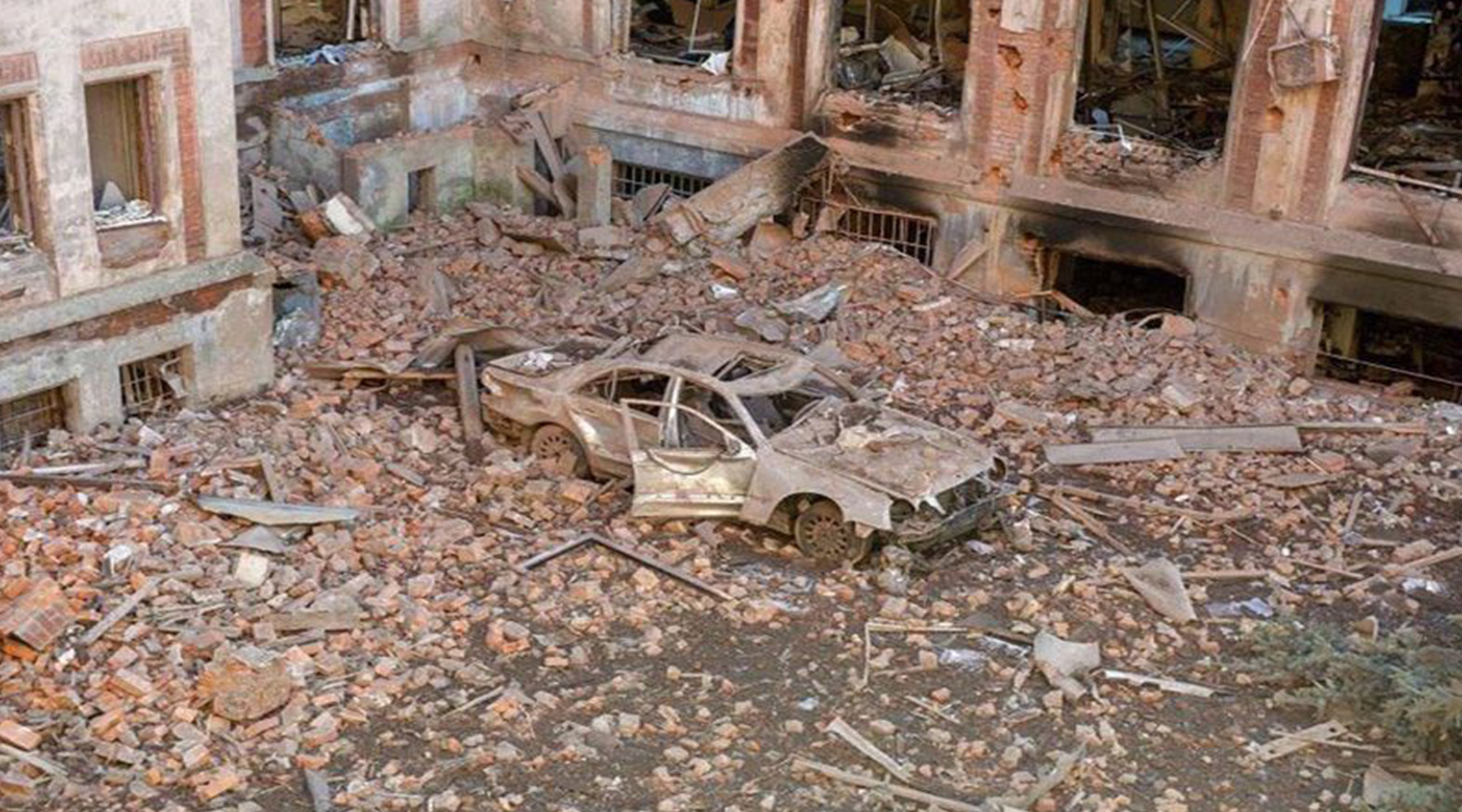

Along with other targeted cities, Kharkiv and its inhabitants found themselves rapidly in the firing line of a wide array of Russian weaponry, including attack aircraft and helicopters, tanks, long range artillery and missiles.

In Ukraine, it's uncommon for most people to have a car, especially students. And by the first week of the war, gasoline had run out anyway, rendering vehicles useless. “The only possible way out was to evacuate by train. But we were afraid to leave because the city was constantly bombed…we thought they would hit the railway station," Jenny says.

“We were trapped in our building for two weeks until we had the opportunity to evacuate. But I was trapped with my best friend, and that helped me stay courageous.”

Jenny’s parents were in another city separated from Kharkiv by the frontline. “My father is a surgeon, and my mother is an OB/GYN, so even if they could have left, they stayed to help people there because they really need it.”

For two terrifying weeks, Jenny, her best friend, and a slowly dwindling group of about 50 students and faculty sheltered inside their dormitory. “We were afraid of staying in our bedroom, afraid the windows would break. We basically lived in the bathroom which felt safer,” she says.

“Many at the University had evacuated as soon as they could, but there were around 50 in my building who couldn't go for some reason. Maybe they didn't have any place to stay, or they were afraid. Or they were waiting for something, like us. We were waiting for the war to settle down, we thought it would be over in ten, 15 days.”

Thankfully, the day before the war broke out Jenny had bought “a lot of food,” so they had supplies for up to a month if adequately rationed. But they started sharing their food with the others who were not prepared.

“People became more generous, everybody was trying to help each other. Nobody left without notice – if they had an opportunity to leave, we would all say goodbye, and wish them good luck.”

Also staying in their dormitory were paramedic students, who took on as much work as they could, including many night shifts. “We became very close, always checking on them, giving them coffee after the night shifts,” Jenny remembers. “They had probably seen a lot, but we never talked about that because it would make them even more stressed.”

“Their courage was extremely inspiring. I saw the paramedic guys risking their lives for others, right in front of my eyes. And they were so tired. I thought, ‘Oh my god, thank you so much.’ I will remember it my whole life.”

On March 1, a missile hit a nearby campus, sending buildings up in flames and blowing out the windows on several surrounding buildings. Then, a second attack on March 2 devastated her University’s economic department. It suddenly felt far more dangerous to stay than to attempt an escape.

“It had become unbearable. We understood we couldn’t stay there anymore. We didn’t know if there were victims in the building that had been hit.”

In a split second decision, the pair left on March 3. A government curfew meant it was forbidden to be outside after 4pm, so there was little time remaining to get to the station. “We had 15 minutes to pack, so I left with only my backpack which had my documents and a laptop,” Jenny says.

They booked a taxi, at a cost of ten times the usual. The 20-minute trip took 40, due to closed roads and collapsed buildings. At the railway station, masses of people crowded the platforms, desperate to get on one of the trains that left every two to three hours. “Usually there were two trains per day, but they were running much more frequently as there were so many people trying to leave,” Jenny explains.

The friends managed to board a newly arrived train, and incredibly they found a seat. “But we took all the children on our laps,” she says.

People continued to board the train until it was double its capacity, and passengers became anxious to go. “Everybody was afraid a missile would hit the railway station…but it had never happened before. We were all just hoping that luck wouldn’t run out today,” Jenny says.

At last, they left Kharkiv behind, destination Lviv – considered the ‘safe city in the West’ (though Lviv was bombed only a couple weeks later). Passengers were told they wouldn’t go through the nation’s capital, Kiev, because of the extreme danger there, but by nightfall the train had stopped at Kiev station to take on more people waiting to leave.

It was night as the train crawled through the Kiev region, explosions sounding in the distance. Passengers were told to turn off their phones and extinguish all light. “We shut the windows and pulled all the curtains to make the train invisible to planes and tanks at night. We travelled very slowly, as silently as possible, making no noise so the bombers couldn't see or hear us, because the frontline was just a couple kilometres away.”

The journey took much longer than usual. “We left Kharkiv around 5pm and arrived in Lviv the next afternoon. My back felt like it was breaking.

“Everyone was trying to save their animals...there were all kinds of animals on the train. People were extremely quiet on the journey, though sometimes there were quarrels between passengers as everybody was on edge.”

The friends were separated when they reached Lviv. Jenny boarded a train to Poland where she had a place to stay, while her best friend went on to Germany.

On the first train, there was a mix of men, women, and children, but Jenny says on the train from Lviv across the border to Poland, there were only women and children. The men were forbidden to leave, because of military duty. “I saw people crying, especially young women with small kids,” she says.

“Some men dressed as women to go to the border, but they were caught by police when they checked their documents. It’s controversial because people consider that men have a military duty…but I left because I was afraid, and they wanted to do the same. It was terrible for them, to know they couldn’t go anywhere. It’s a real tragedy because people were just trying to escape the war with their families.”

After a month in Poland, Jenny became increasingly anxious about her future, and her proximity to the Ukrainian border. “Everybody was thinking ‘what if it gets worse? What if Poland gets involved?’

“In April I started looking for university scholarships overseas, but got the same response of, ‘It's impossible to do it now, maybe wait until September?’ I was like, ‘What do I do with myself?’ I didn’t have the right documents to get a job in Poland.”

While searching for opportunities, Jenny found a scholarship for a language school in Cairns, Australia, a place she had never in her wildest dreams imagined she’d end up in.

By April, Jenny was on a plane bound for Brisbane. It was a very long trip. “I went from Krakow to Helsinki to Singapore to Brisbane, and got lost in every airport,” Jenny laughs. “When I finally got here, my parents could breathe – they were so relieved I was in a safe place.”

When she got on the plane in Poland, it was snowing. Two days later she stepped out of the airport in the only clothes she had – a winter coat and boots – and into the steamy oven that is Queensland in summer. "I was like, ‘Oh my god. It's so hot!’", Jenny laughs.

A Ukrainian family who have helped many others like Jenny, hosted her in Brisbane for two weeks. “They emigrated to Australia more than 20 years ago, so they told me some important cultural things I should know from the very beginning,” she says.

“The mother of this family worked in a shop run by an organisation that provides Ukrainian refugees with clothes, food, and services they need. They helped me a lot, including with better clothes.”

Next stop, Cairns. Culture shock may be an understatement when describing Jenny’s first two weeks in tropical Far North Queensland. “I really enjoyed the nature there, but I was shocked, I saw crocodiles just there on the beach! When I arrived in Cairns it was 40-plus degrees. I had never experienced humidity because we don't have it in Ukraine.”

Unfortunately, Jenny’s skin had a severe allergic reaction to the unfamiliar heat, humidity and tropical flora and fauna. “Nobody could help me, I had to live with that for six months until I left Cairns.”

From her host family, Jenny received a list of scholarships available to Ukrainian refugees eager to continue their university studies, including an Asylum Seeker Scholarship from the University of the Sunshine Coast (UniSC). She applied, expecting nothing, hoping the luck that had got her out of Ukraine alive would extend a little further.

“I got an email response from UniSC, but at first I misunderstood it, thinking I got a partial scholarship,” she says. “I thought, ‘I can't afford it,’ and I started crying. Then I read it again, and understood I got the full scholarship.

“I burst into tears again, because of happiness, and immediately called my parents and grandparents, and everybody was crying, because it's a real opportunity for a better life.”

As the only child and grandchild, Jenny knows how much her safety, happiness and prospects mean to her parents and four grandparents left behind in Ukraine.

“When I got here, they were all so happy – I think my grandmothers had turned even more grey with worry. They all live very close...I'm so happy my family is so united and close to each other. It's so precious. Because when I came here, I realised having a family that supports you is the most important thing.”

Having six adoring adults supporting and loving her from their war-torn country on the other side of the world, Jenny says this is her chance to make them proud, and make her dreams come true.

Now in her first semester at the University of the Sunshine Coast (UniSC), Jenny made the life-changing decision to switch to a biomedical science degree.

“My childhood was spent visiting my parents and grandparents at their work in hospitals – my paternal grandparents are also doctors. But in Ukraine, the salary of medical and scientific workers is extremely low. I never understood why because they have so many responsibilities and they're not paid back.

“So, at university I decided to take up another major as I was good at languages, and foreign languages is extremely popular, well paid, and prestigious in Ukraine.

“But when the war started – when I saw the paramedics sacrificing themselves for other people, even though their life was in danger, it really affected me,” Jenny says, close to tears. “I can't even describe how much I was moved. It changed my entire outlook, and I understood I have a passion for medicine and biomedical science.

“I saw my parents’ helping others. I saw my grandparents being proud of them. And I want my parents to be proud of me.”

And, after the trauma of her extreme allergy to heat and humidity in Cairns, Jenny also hopes by taking up biomed she can help others from cold climates who struggle with similar problems.

One common thing Jenny has heard many times from people, even total strangers when she’s walking down the street, is “your face is so serious, you never smile.”

It’s something most Eastern Europeans can relate to.

“In Eastern Europe, we even have a proverb that translates, roughly, to ‘smiling for no reason is a sign of stupidity,’” Jenny laughs.

“If you’re insecure about your future, you don’t smile. But when I came here, I understood you can smile without a specific reason because you have a good life, a good job, a good education, and you know that tomorrow everything will be okay, you’re not afraid. You can walk down the street and smile at the world and the people you meet.”

What a difference a year can make

“I can't really believe this is happening to me, that one year ago I didn't know what to do or what would happen,” Jenny says.

“And now, I am studying in Australia, I have people supporting me, I have an institution which gives me access to education, I have opportunities, safety, and a great network of people. And I'm just so grateful for that.”

Media enquiries: Please contact the Media Team media@usc.edu.au