When I lived in Kalimantan in Indonesia in the 1990s and later in Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, I would often wake to toxic, smoke-filled skies. The air would be filled with the distinctive smell of burning peat, as farmers cleared tropical peat swamp forests to make way for oil palm plantations.

Airports and schools would close, and hospitals would fill with people in respiratory distress – myself included. Global greenhouse gas emissions would spike because peatlands are the planet’s most carbon rich ecosystems.

Throughout the world – from the subarctic peat bogs to the tropical peat swamp forests – drainage and rising temperatures are driving increasingly frequent and intense fires, releasing emissions from millions of hectares of peatlands and destroying irreplaceable biodiversity.

Uniquely, an Australian subtropical peatland ecosystem exists that is not only resilient to the frequent bushfires, but actually needs fire to survive.

What are peatlands and why do they matter?

Peat is poorly decomposed plant matter that builds up over millennia in waterlogged environments.

When wet, which is the natural condition, peat can only burn under the most intense fires. As the precursor to coal, however, dried peat is highly flammable. Peat fires can smoulder underground for years until all the peat has burnt away.

We’ve been researching Australian subtropical peatland ecosystems which need fire to survive.

These peatlands were observed by a British scientist flying over K’gari (Fraser Island) in Queensland in 1996, who recognised a characteristic outline suggesting there were peat bogs below.

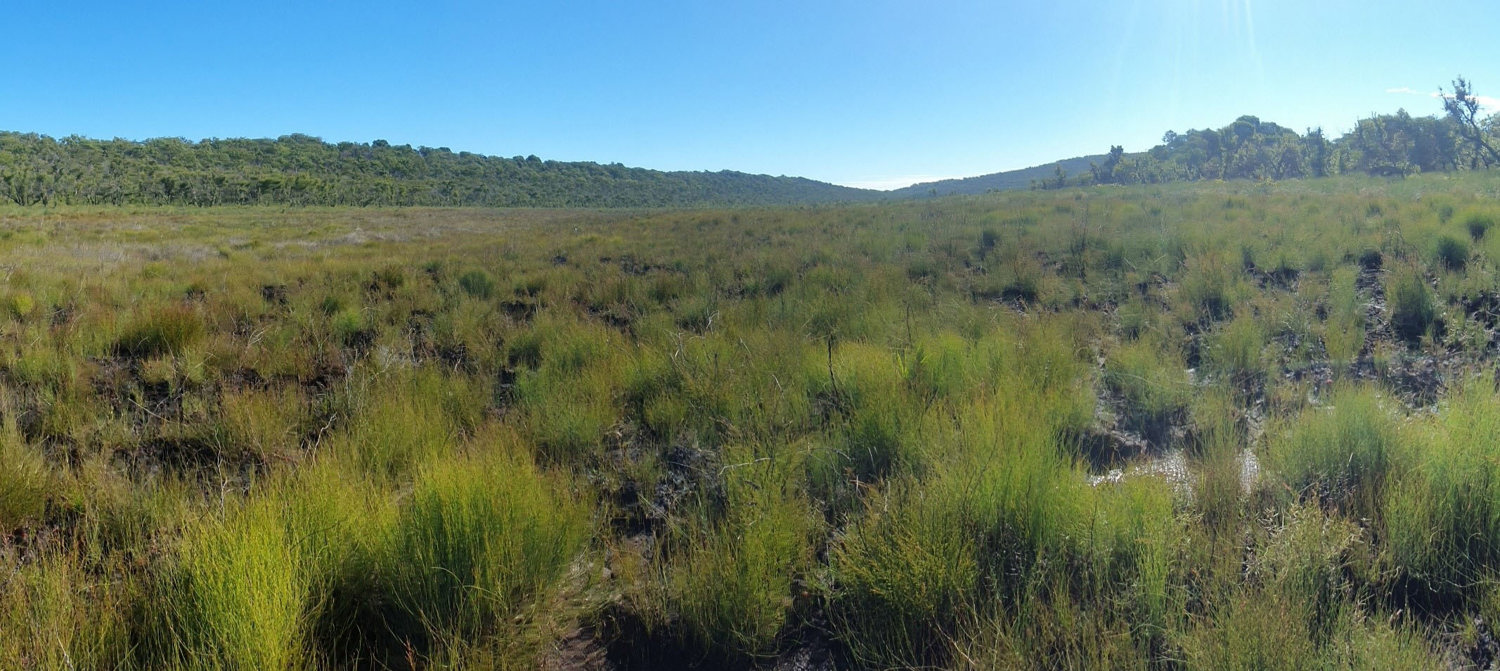

They were discovered to be peat swamps dominated by the peat-forming plant known as wire rush, Empodisma minus.

Since then, thousands of hectares of these peat swamps have been identified along the ancient sand deposits of the Australian coast from Queensland to New South Wales.

There are many other types of peat swamps and bog in Australia, from the sphagnum bogs of the Australian Alps to the buttongrass moorlands of Tasmania. These are badly affected by fire.

What’s so special about subtropical peat swamps?

These Australian peat swamps hold significant carbon stores in peat deposits up to eight metres deep.

Layers of charcoal are visible throughout peat cores, showing the regular occurrence of fires over many thousands of years.

Their waters shelter rare and endangered fish (including Oxleyan pygmy perch and honey blue-eye), frogs (such as Cooloola and Wallum sedge frogs) and crayfish (such as the sand yabby Cherax robustus), as well as dragonflies, beetles, midges and bugs.

Subtropical wire rush swamps (in places such as K'gari and Cooloola in Southeast Queensland, for example) require fire to suppress other plants – such as dodder, tea trees and banksias – in order to thrive.

Wire rush regrows rapidly after fires from spreading rhizomes (underground roots).

It is a perennial, forming dense masses which eventually die at the centre.

This central detritus is overgrown by foraging roots, forming water filled depressions, eventually creating pools many metres wide.

These wire rush-ringed pools form the distinctive patterns first reported on K’gari.

Intact, long dead, wire rush roots and leaves can be seen deep down in peat cores thousands of years old, along with charcoal and seeds of other plants.

This shows this plant matter doesn’t break down, even after thousands of years. Over many millions of years, peat can form coal – about one metre of peat will turn into about 10cm of coal.

A thick, moist root layer is crucial to fire resistance

Peatland plants are tough and toxic to prevent them being eaten by animals and this slows down microbial decomposition. So instead of completely breaking down, they form the brown mushy substance we call peat.

The plants are rich in carbon-based compounds such as tannins, the chemicals that give black tea its dark colour, creating the distinctive, acidic blackwaters seen in all peatlands.

Wire rush roots have dense hairs that absorb water and nutrients like a microfibre sponge.

These roots grow up, not down, to rapidly scavenge nutrients from leaf litter. They cover the peatland floor, which protects the underlying peat from drying out, and from catching fire.

This thick, moist root layer is crucial to the fire resistance and resilience of the wire rush swamps including the aquatic fauna.

The resident sand yabbies dig multiple burrows through these otherwise almost impenetrable roots to the wet peat below. These wet burrows provide a safe refuge for the fish, frogs and other animals during droughts and fires.

As fires get more intense, we are getting more concerned over the future of these peatlands. The severe 2020 fires on K'Gari resulted in some peat deposits burning down to the sand below.

We still need to know more

Our research group is studying these peat swamps. We want to know how deep and dense the peat is, how animals and plants have adapted to the acidic water, how plants, animals and microbes resist and recover from fires, and whether they can survive hotter and more frequent fires.

The wire rush peat swamps of the subtropical eastern Australian coast are unique and fragile. But they face pressures from urban and agricultural expansion, road construction and climate change. It is important we protect them and the unique ecosystems they harbour.

By Professor Catherine Yule, University of the Sunshine Coast

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media enquiries: Please contact the Media Team media@usc.edu.au